Cybertracker 2019:

The line of tracks were turning into round dimples under the falling snow. A track is simply a disturbance, a change to baseline, and these tracks were clearly the footprints of a four-legged animal – coyote or bobcat came to mind. Under the rules of the CyberTracker Evaluation I could not use a measuring tape or explore beyond the test area for additional tracks and signs to identify the maker of the tracks. The evaluation included 50 test questions in total, and the steady fall of snow in the Cascade mountains of Oregon, U.S.A. was adding a layer of challenge I had not trained for.

A certified Master Tracker has completed a CyberTracker evaluation with 100% accuracy. Inspired in the 1990’s by an indigenous Kalahari tracker – !Nate, and a Harvard Associate of Human Evolutionary Biology – Louis Liebenberg, the CyberTracker test was developed to evaluate and communicate an individual’s tracking ability. The test originated to encourage tracking as a paid profession and allow the San Bushmen or Kalahari First Peoples, to get jobs in ecotourism, wildlife monitoring, scientific research or as rangers in anti-poaching units. With a long history of tracking as traditional hunters, the Kalahari First People were able to verify their skills as expert trackers through the CyberTracker evaluation without the need for a degree, or to read and write (Liebenberg, 2013).

Tracking first intrigued me as a child reading Tom Brown Jr’s book The Tracker in elementary school. In 2008, I had the opportunity to attend a class at Tom Brown Jr’s Tracker School and I was hooked by Tom’s infectious passion for tracking. Tracking is great fun and it’s a joy to connect to the bigger picture of what’s happening in any given environment, but it is the process of tracking that most intrigues me. Tracking is both an art and a science that requires detailed analysis and imagination; in other words, it is a holistic science. A holistic approach values and weighs information from multiple ways of knowing, including the analytical and intuitive, or so called right and left brains.

Cybertracker question #22: Who made these tracks and at what gait? The size of the snow dimple, the evenly spaced stride, and the way it meandered through the tall, coniferous forest could have been either canine or cat. Clear evidence of decisive digits or claw marks were long gone under snowfall. My hand hovering over the track I cleared my thoughts for a moment to see if any feelings, images, or words came to mind as I recreated the movement of the animal in my mind’s eye. The tracks had the feeling of cat, but my gut had been wrong before. I did not want to stake my conclusion entirely on intuition. We were close to a busy highway and a steady stream of cross country skiers and their domestic dogs moved nearby. Coyote seemed more likely based on a rationale that bobcats tend to be more secretive, however, I had been burned by answers based solely on rationale too. With the clock ticking and snowflakes accumulating, I made a decision. I whispered “coyote” to the person collecting test answers and moved on to the next question.

CyberTracker question #23: “What animal is it and which direction is it going?” Glancing at the tracks stretched across the top of a fallen log I immediately knew it was bobcat, and that this was the same animal I had previously dubbed coyote in question #22. Aware of my first impression, but cautious not to trust that completely, I scanned the area for tracks and sign to support/negate my hypothesis of bobcat. The round tracks were too snowed in for detailed analysis but were in a line of direct register prints. I could see where it had walked around a branch sticking out of the log and sat before jumping to the ground and heading West. The track size, gait, behavior and my intuition all screamed bobcat. I gave my answer and participants gathered as a group to review answers to the questions in the area with a Master Tracker. We went through the entire scientific process from our hypotheses, data analysis, conclusion and debate with peers all within a fifteen-minute window. It was indeed a bobcat. Data I had once gathered for a university research study took decades to yield conclusive results. By comparison, basic wildlife tracking is a speed science.

The relatively quick answers that a Master Tracker can give in response to questions about tracks and signs, lends tracking as a valuable tool to develop accuracy in analytical and intuitive muscles of perception. Beyond the utility of tracking in conservation biology, search and rescue, hunting and environmental education, tracking may serve as fertile ground to train in Holistic Science.

Holistic Science:

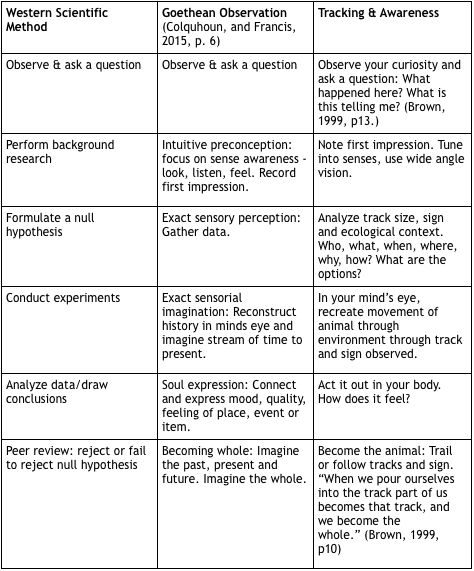

Tracking is not necessarily a linear process. To identify an animal or a series of movements through tracks a process occurs that could be described as parallel to Goethean observation methodology – a method of inquiry regarded as holistic. Both require intense attention to detail and precise imagination (Table 1). Tracking is much more than identifying who left a footprint on the ground; it includes awareness of the landscape as a whole. “To understand the track is to understand the animal and its relationship to the land. It is also to understand our own place in the natural world (Brown, 1999, p 10).”

Table 1. Science as a replicable process of inquiry from three different lenses.

From right to left: Kgum, Xhoeta, Tswana, Bao. Photo by Rachael Pecore-Valdez.

Botswana:

My training as a tracker brought me to Botswana in March, 2018 where I joined Dr. Nicole Apelian and Jon Young with EcoTours International to meet a group of Kalahari First People (Nharo) who are working to keep their culture’s traditional skills alive, including tracking. Aside from visiting zoos as a child in North America I had no direct experience with Southern African wildlife. I was in completely unfamiliar territory which gave me a window to observe the process of tracking in a new environment.

As our small plane descended toward a lodge, the only building in sight, I saw the tall necks of giraffes above the flat expanse of savanna woodland extending out to the horizon. Giraffes were one of the animals I most wanted to see up close, and I squealed in excitement. We were met at the runway by a group of thirty people, singing and clapping as we stepped off the plane onto the finely packed sand of the Kalahari Desert.

After meeting and greeting each member of the group from toddlers to elders, we were warned not to leave sight of the lodge without experienced guides or to disembark from any vehicle without permission or before scanning the area carefully. This was the bush where lions, snakes, and all manner of things could kill the unaware. My awareness instantly peaked. My body became alert, and senses came alive with a feeling on the edge of fear and excitement of the unknown.

In fact, there were lions lurking just behind the lodge. Thankfully they were on the other side of a tall fence, meant to humanely contain lions who were hunting cattle until they could be relocated. The sound of their deep belly grunts, especially before a meal, became part of the daily backdrop of Kalahari sounds. Listening with keen attention to the sounds of the birds and insects, is one of the keys to survival and tracking in the region. Reading the alarms and posture of birds is an instant indicator of where danger lies. The First People listen to the environment with surround sound awareness all the time. Once, when asked where the nearest free-roaming lion was every person in the group immediately pointed in the same direction. They knew because they had to know. Jon Young shared a story that the First People tell their children, “A long time ago, a lot of our people were killed by lions.”

Each morning we walked with youth and elders who pointed out various edible plants and animal tracks like honey badger, wildebeest, kudu and even the tracks of giraffe who had visited the watering hole in the early morning. My brain quickly began to form search images and categorize the new dents and divots in the sand by size and shape. The marks in the sand, like the black and white shapes in the hidden image (Image 1), did not change but how my mind organised and translated the meaning of these shapes did. With limited experience, and a hope that biased almost all hoofed tracks in my imagination into a series of giraffes of all sizes, my mind was quick to fill in the unknowns. I had to remind myself to pause, and examine the tracks and surrounding environment more closely,“(1) if we lack search images we may not recognize the existence of something in the environment around us; (2) if we have misguided images or inaccurate information, we will project a misguided or inaccurate perception (Young, 2007, p 57).”

Image 1: Do you see the giraffe? (Bortoft, 1996, p 50).

I did not see giraffes up close that week, but after saying goodbye to our Nharo teachers we flew North to the lush Okavango Delta where the diversity of wildlife including giraffes, bee-eaters, waterbuck, warthogs, tortoise, mongoose, elephants, and zebra is truly astounding. Early one morning, I awoke with a clear image of a lion in my mind’s eye. The hippos were grunting loudly not far away. Our guides had warned us not to leave our tents until they let us know it was safe, so I lay comfortably in my cot watching the dawn brighten. And then I heard the deep belly grunt of the lion. It sounded far away, but as we journeyed out into the delta that day to track, I searched for images of lion prints along the sandy roads. Several miles from camp, we spotted feline tracks and debated the size and difference between lion and leopard prints. Following the general direction of the tracks from the relative safety of an open-air land cruiser, we headed further into the delta. At one point we pulled over to let a supply vehicle pass and as is the custom, stopped to chat for a minute. The driver shared that two males lions were spotted up the road the previous day. Eventually, we had to turn around due to a chest-deep puddle in the road, and leave the lion tracks to the elements. While I cannot say why or how I awoke knowing that a lion was around, I knew that two short weeks of engaging my senses and soaking up the environment had tuned up my intuitive perception. While I wouldn’t stake my life on intuitive knowledge alone, the presence of a lion was confirmed without a doubt by tracking, listening to the landscape and local knowledge.

Multiple Ways of Knowing:

The process of tracking – from intuition to physical evidence in the case of the lion, or from physical evidence to intuition in the case of the bobcat – exercises multiple ways of knowing. To sharpen our empirical tools, whether as a scientist or artist, tracking with a master tracker will help develop accuracy and trust in both analytical observation and intuitive ways of knowing. The training of those muscles, to balance the analytical and intuitive ways of gaining understanding, the left and right brain, intellect and heart, art and science, or feeling and thought… leads to a holistic approach and ultimately sound decision-making. When knowing whether a lion is present or not could mean life or death, every tool we have to find answers quickly and accurately becomes important. The art and science of reading tracks and signs is useful as a training tool to fine-tune awareness. Whether the threat to life is a lion or a global challenge like climate change, considering all modes of knowing will help to ensure a complete picture.

Photo: Can you spot the feline? Who else?

References:

Colquhoun, M. Reading Nature as Text, New View.

Bortoft, H. (1996) The Wholeness of Nature, Lindisfarne Books.

Brown, T. (1999) The Science and Art of Tracking, Berkley.

Young, J. (2007) Animal Tracking Basics, Stackpole Books.

Liebenberg, L. (2018) CyberTracker.

Liebenberg, L. (2013) The Origin of Science, Cybertracker.

Liebenberg, L. (2000) Tracks and Tracking in Southern Africa, Struik Natu re.

Franses, P. and Wride, M. (2015) Goethean Pedagogy, Emerald Group Publishing.